3rd Katrina Day

The impact of Hurricane Katrina will change, in a profound and enduring manner, one of the cradles of African-American culture.

Lance Hill, Director of the Southern Institute for Education and Research at Tulane University

Laissez les bon temps rouler!

Our meeting point is in the Lower 9th Ward, one of the neighbourhoods worst hit by Katrina. It is here that the commemorative march for the third anniversary of the hurricane will start.

The atmosphere is intense. Somebody pins up lists showing the names of the 853 victims of Katrina on the new levee wall of the Industrial Canal (officially the Inner Harbour Navigation Canal), built to protect the neighbourhood from future flooding.

The march sets off. Drummers beat out a rhythm as marchers demand their civil rights and call for affordable housing. Aid efforts in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane suffered from a lack of coordination, with the government failing to provide the necessary help to those who were unable to leave. One of the slogans that can be heard is “Three years later and still no change!”. At present, New Orleans is at 72% of its pre-Katrina population of 455 thousand.

The music of the Rebirth Brass Band provides the march with a joyous soundtrack, but the voices of those taking part are less upbeat: “My brother-in-law was killed during the hurricane aftermath”, says one. “The police shot him seven times in the back, for no apparent reason. He suffered from mental health issues”. New Orleans is in need of much more than just new flood walls and housing – the city’s very social fabric needs rebuilding.

New Slaves

WJ editorial

Slavery is the dirty habit Louisiana never really kicked. Here, an ambitious project set to transform New Orleans into a theme park for rich WASPS sees the habit resurface in “innovative” new forms.

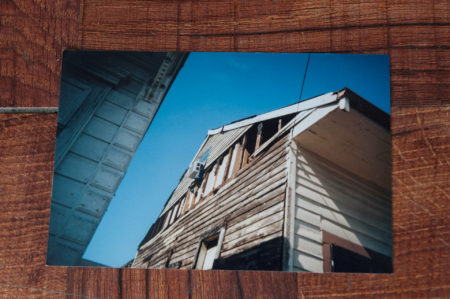

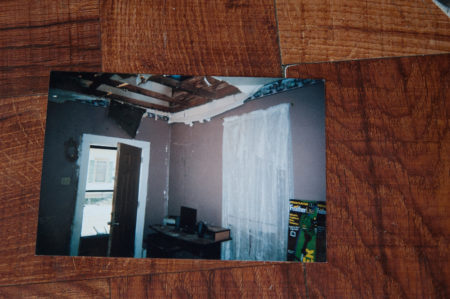

A year on from the worst natural disaster in US history, fewer than 200 thousand inhabitants (out of a total of half a million) have returned to New Orleans. Entire neighbourhoods still lie in ruins and only half of the city’s schools and a third of its hospitals have reopened. 60% of houses are still without electricity, while the city’s poor and black residents – who once made up two thirds of the population – account for the majority of those still missing. In many cases, the houses they once lived in have been torn down and there are no plans for their reconstruction.

The situation is ripe for exploitation by those aiming to drive out the city’s black and poor and replace them with affluent whites. Talk of rebuilding the city’s historic black neighbourhoods has come to naught: for now; only the picturesque and tourist-friendly French Quarter and the stately white villas of the historic Garden District have been restored to their former glory. Even Bourbon Street is pervaded by a sense of neglect and abandonment. For Boysie Bollinger, a personal friend of president George W. Bush and one of the leaders of the local business élite tasked with leading the reconstruction efforts, however, things could scarcely have worked out better. His shipbuilding business is back up and running despite losing the majority of its workers to the hurricane (some died, others were displaced). They have been replaced by Mexican and Filipino, many of them illegal immigrants, who are prepared to work day and night to avoid deportation and are thus much more vulnerable to blackmail. “Katrina will lead to a profound change in New Orleans culture”, says Bollinger, predicting that “the black workforce will soon be replaced by Hispanics, who are harder workers”.